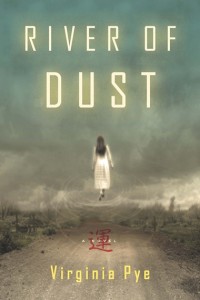

Virginia Pye and I also share an important bond: we’re both lucky enough to have our work published by Unbridled Books. When we met at the Virginia Festival of the Book in March 2013, she kindly agreed to respond to a few questions about her forthcoming work, River of Dust, a beautifully lyrical novel inspired by her grandfather’s journals, written while he was a missionary in China in the early 20th century. This debut novel has already won an important accolade, having been selected as an Indie Next Pick for May 2013. Pye, aside from having taught writing at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University, served three terms as president of James River Writers, a literary non-profit in Richmond, Virginia. Her short stories have won awards and appeared in numerous literary magazines, including The North American Review, Tampa Review and The Baltimore Review. There is more information about Virginia Pye at Unbridled Books, as well as her author site.

Huergo: How would you describe your writing process?

Pye: I have written for many years, stopping only when my children were young. River of Dust is my sixth novel, though the first to be published. I tend to ruminate on a story and characters for a while before I begin to write it. I jot down an outline. Nothing strict, but something to follow, heading towards key moments or turning points. I then dive in. I write every day and have for some time, unless I’m distracted by travel or family. When I was working on River of Dust, I was so possessed by telling the story that it woke me before five a.m.. I was at my desk with a cup of coffee before sun up and could write for two hours and then take my son to school. I’d return to it in the daylight and press on. I tend to write a full first draft of a book, then go back and rewrite extensively through many more drafts. The whole process can take years, but luckily, there’s nothing I’d rather be doing.

Pye: The most difficult aspect is being able to see the work clearly for what it is, not for what I hope it will be. Like many writers, I have a love/hate relationship with what I write. I can be enamored of something one moment, and then feel chagrined by it the next. What’s hardest is to find that clear-eyed balance where you can see where you have succeeded, but also where you’ve fallen short. Hemingway said, “The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shock-proof, shit detector.” For me, that’s taken years to develop, and I’m still working on it. And, by the way, there’s a danger in sharing work too early. A writer can become hopeful and excited by her intentions and share it. That’s never a good idea, because criticism can be confusing and can throw you off track. It’s better to really polish the work and give it its best shot, and then venture out with it.

Pye: I’m extremely lucky because I have a supportive husband and family, and I live in a community where there’s a sense of space and time in which to write. My life is not overly pressured. I used to teach writing, but not these days. Also, for years, I helped run a literary non-profit. But for now, I can say I just write. I tend to be disciplined about my time and go to my desk daily, which I consider a great privilege.

Huergo: What’s your next project?

Pye: I’ve written many drafts of a novel about a family in Cambridge, Massachusetts—which happens to be where I grew up—at the time of the student take over of Harvard in 1969. For some reason, I’ve been trying to write that event into a novel for decades. It fascinates me. This novel is about two sisters, one of whom ends up inside the administration building during the take over. The girls’ father is Dean of Students, and his job is to bring the kids out of the building safely. Once again, as in River of Dust, I’m interested in the conflicts within families of the dominant class. In this case, they are not missionaries, but “the establishment.” I’m interested in how the next generation goes to great lengths to define themselves in opposition to their inherited status. In other words, it’s a novel that comes out of the sixties. And, although I wasn’t of that age, I know how it tore apart families and has echoes to this day.